Feeding seaweed to cows should be Ireland’s highest priority in the fight against climate change

This week has seen initiatives on both sides of the border aimed at tackling Ireland’s contribution towards climate change.

The Irish government published a Climate Action and Low Carbon Development bill, committing the government to a ‘national climate objective’ of being carbon neutral by 2050, and a 51% reduction in emissions by 2030.

In the north, there were not one but two pieces. The first, introduced by Green Party Northern Ireland leader Clare Bailey, proposed a net zero target by 2045. Another, less stringent, bill is being proposed by Environment Minister Edwin Poots, aims to reduce emissions by 82% by 2050.

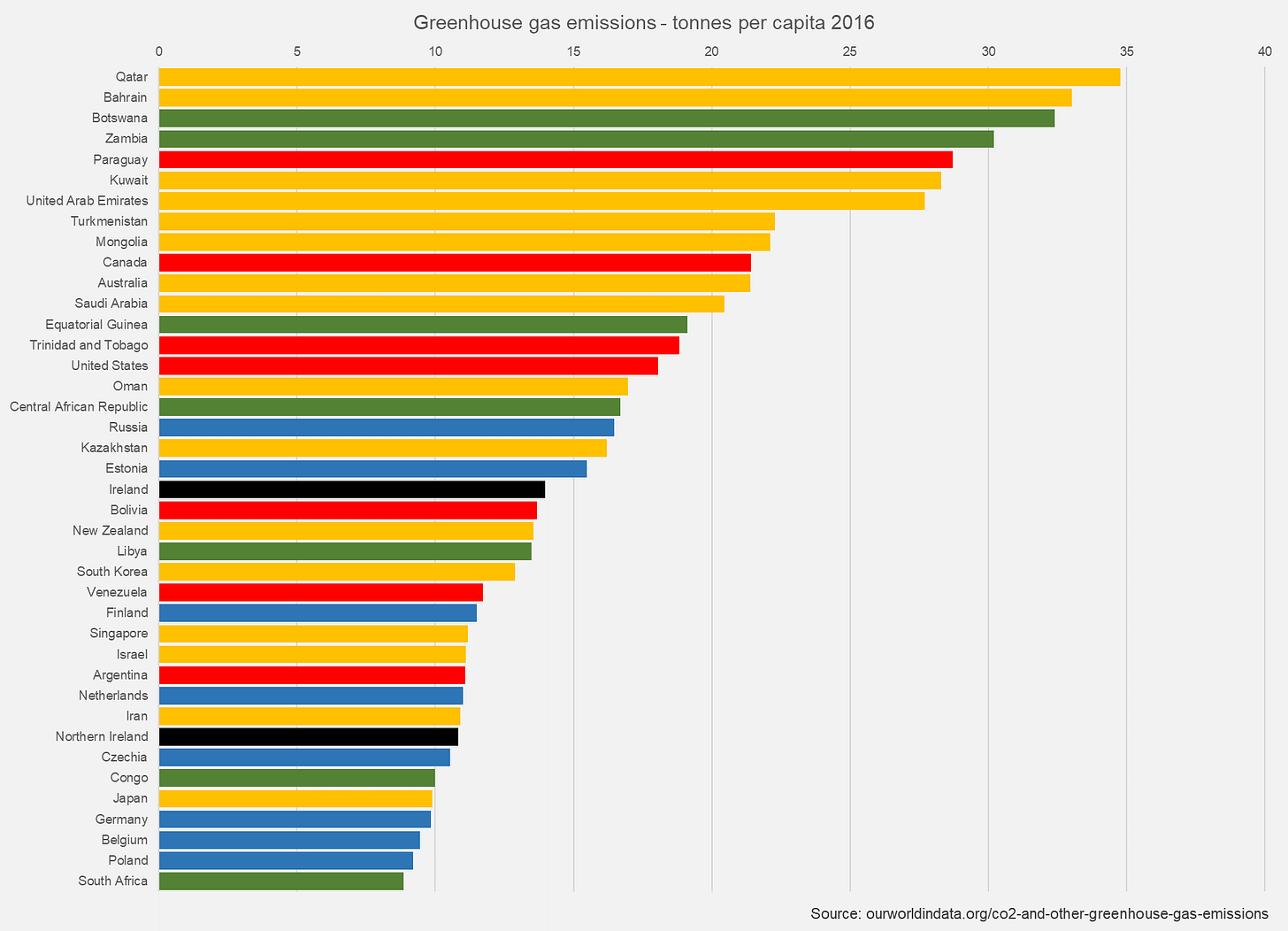

On both sides of the border, greenhouse gas emissions in Ireland are among the world’s highest. In 2016, greenhouse gas emissions in Ireland per capita were the third highest in Europe, after Russia and Estonia. If it were a separate country, greenhouse gas emissions per capita in Northern Ireland would be the sixth highest in Europe.

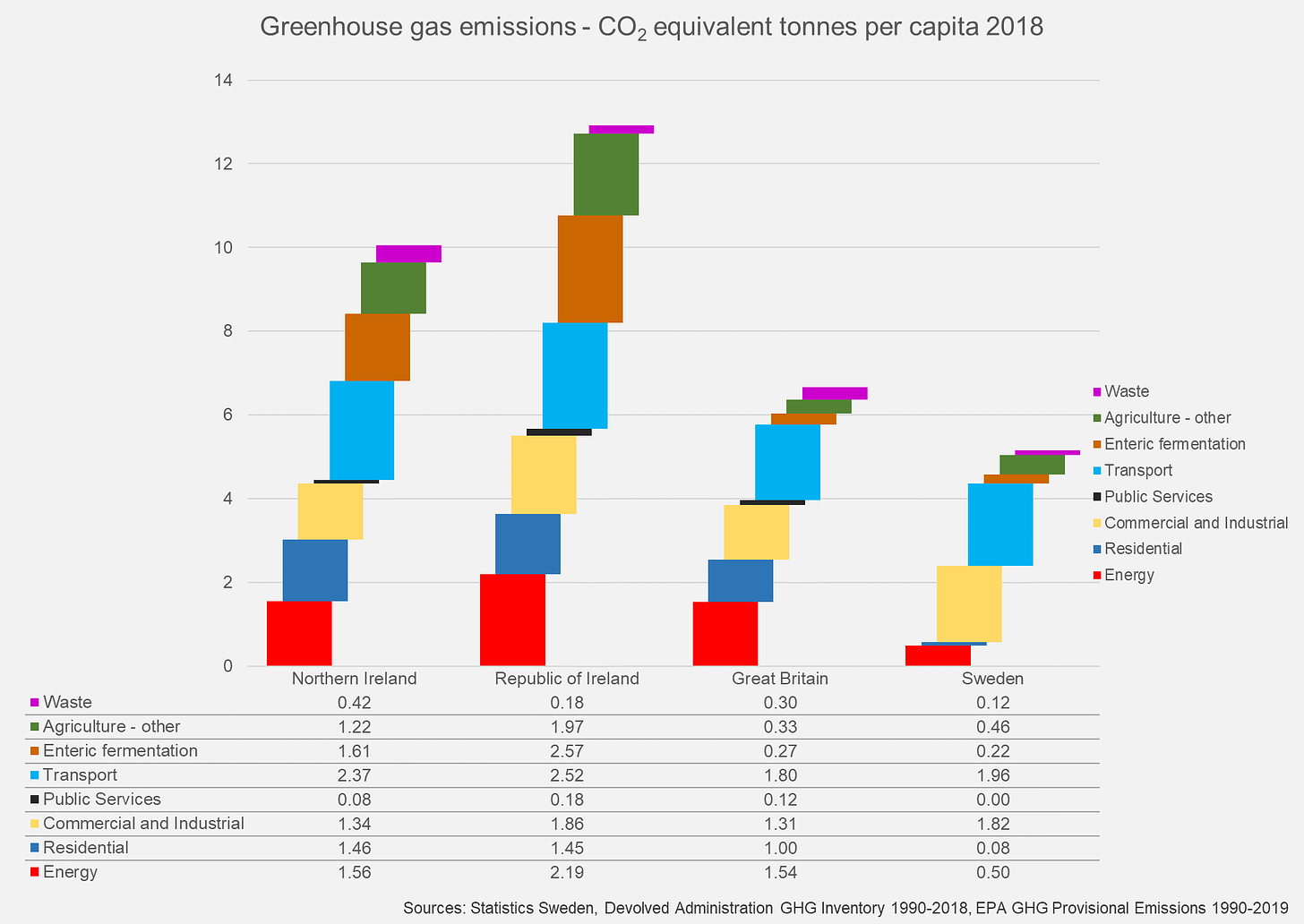

Enteric fermentation (burps and farts) of livestock, predominantly of cows are the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the Republic, ahead even of road transport. In Northern Ireland enteric fermentation is the second highest source of emissions after transport, but it is still a huge contributor towards emissions.

The chart below shows the composition of greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 for the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Great Britain and Sweden, the country with the lowest per capita emissions in western Europe. Note that these figures don’t include emissions from land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF). North and south, the degradation of peatlands means that greenhouse gas emissions may need to be adjusted upwards.

The outsized contribution made by enteric fermentation methane emissions on Ireland’s emissions is obvious. Across the island, enteric fermentation emissions in 2018 were 15.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent. This is more than the combined total of all greenhouse gas emissions from many nation states, including Moldova (11.8 million tonnes), Slovenia (11.0) and Jamaica (9.6).

According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, enteric livestock emissions from cattle per capita in the Republic of Ireland in 2016 (2.22 tonnes CO2 equivalent) were the fourth highest in the world, behind Uruguay (4.19 million tonnes), New Zealand (3.45) and Paraguay (2.22).

If it were an independent country, Northern Ireland’s per capita enteric fermentation emissions from cattle (1.44 million tonnes CO2 equivalent) would be joint sixth with Argentina, behind Mongolia (1.48).

However, the outsized contribution that enteric fermentation in Ireland makes to climate change provides an opportunity to make a dramatic impact on the effort to decarbonize the economy.

Research published on St. Patrick’s day this year demonstrates the impact that adding red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) to cattle feed could make to methane emissions.

The research found that adding Asparagopsis to feed could reduce emissions by 80%, without any adverse effect on the quality or taste of the meat. It adds to previous research showing that Asparagopsis had no adverse impact on the quality of milk.

It is currently difficult to produce Asparagopsis taxiformis, but attempts are ongoing in an attempt to enable production at scale.

If Asparagopsis was widely used in Irish agriculture, it could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by over 10 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, equivalent to eliminating the entire emissions of countries such as Slovenia or Jamaica.

Feeding seaweed to cows is the lowest hanging fruit in the fight against climate change in Ireland. The Irish government and the Northern Ireland Executive should put efforts to scale up Asparagopsis production at the very top of the agenda in the fight against climate change.